INTRODUCTION

Visalia is a small city in central California.

In this particular story, some of the events were real. When my wife and I moved into this house, a few strange things began to happen: noises, such as slamming doors and music coming from nowhere, along with other mysterious little details. Still, the most terrifying thing happened when my wife was in the kitchen and I was in my room. While listening to a soft rock radio station, the music became louder and louder. It was very spooky. After that, it happened a couple more times.

The part about my daughter and my grandson was real, too.

But it’s not a horror story. It’s a funny one.

*****

Before I signed the rental contract, the landlady told me that an eighty-six-year-old man had died in the first bedroom. She said she needed to disclose it before I moved in, so I wouldn’t quit suddenly without signing a thirty-day notice.

At the time, I didn’t pay any attention and disregarded the comment as useless and unimportant. Later, through the neighbors, I learned that the man had lived there for 15 years. After that, three new tenants moved in and out in rapid succession.

The house was old and unattractive, with a garage attached to the kitchen and living room. The family room was next to the dining room, with a narrow hallway and three bedrooms. The floor plan could have been better. The kitchen and dining room featured dark brown paint, carpet, and vinyl flooring. The house could be the ugliest house on the block. I couldn’t find anything attractive or pleasant about that house, but I’ve never been a person with many demands. Therefore, I signed the contract.

After a few weeks, the house was finally home. I didn’t care about how ugly it was.

One day, I was alone in the house, watching TV in the living room. The volume was low, and it was early at night when, suddenly, I heard the radio turn on in one of the back rooms.

I heard a male voice for a couple of seconds. I turned the lights on and went to investigate. I checked in my bedroom, where I had an alarm clock, but it was off. I had another radio, but it was unplugged. I thought it was bizarre, but I returned to watch television.

As the days passed, my wife and I continued to hear normal household noises, such as wood creaking and expanding or wind slamming doors.

Another day, I was reading in bed around 2:00 am when I heard the patio sliding door vibrating for a few seconds. I thought it was an earthquake, but nothing else shook. I convinced myself that my dog, Diego, was pushing the glass door. I wanted to avoid entering the hallway and passing the older man’s room at 2:00 am.

One morning, my wife was cooking in the kitchen and listening to music on the radio. I was in my room when the music suddenly became too loud. I jumped and ran straight to the kitchen. My wife had a look of terror. From there, we both could see the stereo system in the living room—the volume knob turning up by itself as far as it could go.

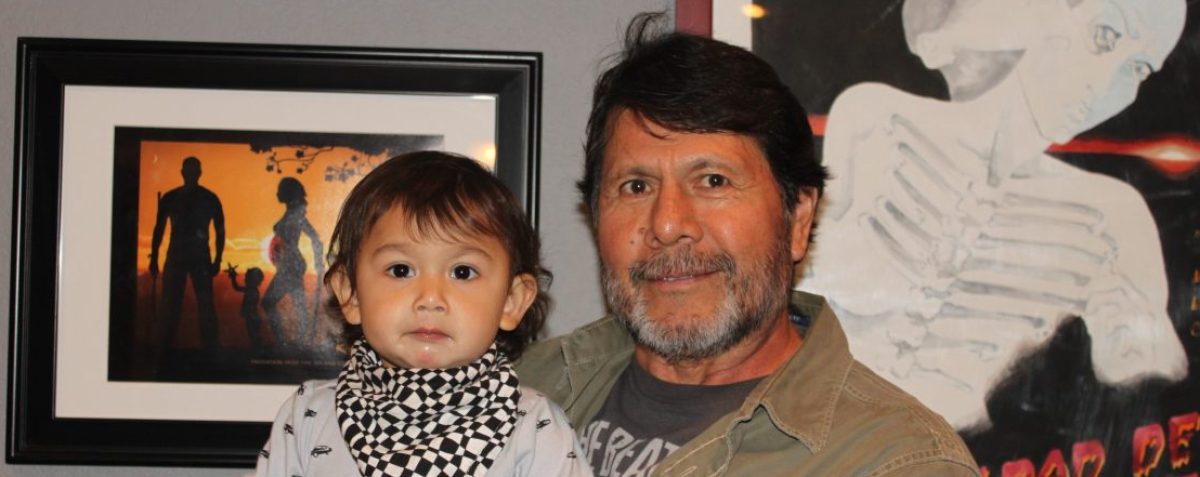

When my daughter and ten-month-old grandson, Damian, visited for a week, I put them in the old man’s bedroom. At first, she said it was warm and comfortable, and she had no complaints. They were happy, and I was pleased.

My grandson was handsome and intelligent, just like his grandpa.

But one night, my daughter came into our room carrying her son.

“Dad, somebody’s moving the bed. Even Damian woke up. We’re staying in your room now.” Then, she asked me to bring our inflatable mattress from the living room to our room. I stood bravely and confidently, but my knees shook when I passed that room.

The following day, I knew I had to confront the old man. I needed to show I wasn’t afraid of him and wouldn’t run away like the other tenants. After all, he wasn’t the one paying the rent. I moved my computer from the garage to his room. That way, I would have to spend more time in that room.

After my wife left for work, I asked him why he was still in the house. I kept talking to him for a few more days, sometimes even in Spanish, but it appeared he was gone. Or maybe I scared him off, or perhaps he never existed at all.

When I had almost forgotten about him, that’s when I saw him.

A mirror hung on the bathroom door; when closed, I could see that mirror and the one above the cabinet sink. So I could see my body, front and back, simultaneously.

That’s when I saw him. I was in shock but not afraid. It took me by surprise; I jumped back, and in the blink of an eye, he wasn’t there anymore. I saw him, but I wasn’t sure whether he was inside the mirror or behind me. He was wearing a light blue suit and a tie. He looked harmless.

“So you’re here after all.” I said, “I hope you’re not shy.” What’s your name? Come on, man, I know you already know my name. Tell me yours.”

“My name’s Peter Shelby,” he answered softly, in a hollow, tired voice. Instead of getting scared, I got genuinely excited. “Tell me, are you with God? Have you seen Him?” I asked him.

“Ha! I was eighty-six when I died. I was baptized and received my First Communion. I gave the church a small fortune in donations. But God was nowhere to be seen. I have tried my whole life to avoid breaking the Ten Commandments. And it was all for nothing. I still hope He shows up.”

“You might be in Purgatory, and God could be undecided on what to do with you. Maybe you’re paying for some pending sins. Who knows?” I said.

“I hope you’re right because it’s boring here. That’s why I was making noises and trying to manifest my disappointment. I wasn’t satisfied with this situation.”

“But why did you have to scare my daughter?”

“You were not paying attention, and that was frustrating. Being alone, bored, and ignored, I couldn’t take it anymore. Tell your daughter I’m sorry.”

“No, you tell her yourself. No, wait, leave her alone. Never mind. But answer me this: what’s your purpose in life? I mean, in death?”

“I have no idea. I think I need to do something, but I’m not sure what. My wife died three years before me. We were happy in this house. We spent our best years here.”

“And where do you think your wife is?”

“She must be in heaven, I guess. She was a much better person than I was. I wish I could communicate with her, be with her, and maybe I can ‘die’ in peace.”

I started to feel relaxed, almost as if I were in a normal situation.

“Okay, next question, do you eat, sleep, take showers, brush your teeth, or go to the bathroom?”

“No, no, no, no, and no.”

“Can you cross walls or doors? Can you touch me or hit me? Do you touch the floor when you walk?”

Yes, I can cross anything. No, I cannot hit you, although I tried a few times, ha, ha. I float a couple of inches above the surface; I don’t need to sit or rest because I don’t need any energy. I’m dead.”

“I just need to tell you something; you cannot appear or manifest yourself in any way while my wife is here. Otherwise, she’ll bring the priest with his holy water and won’t rest until she makes you disappear.”

“But she seems to be such a nice lady.”

“Well, just consider yourself warned. Oh, one more thing: How should I call you, Peter, Mr. Shelby, Poltergeist, Mr. Ghost, or what?”

“I don’t care. Let’s be friends and make the best of it, okay?”

“Is there anything I can do for you? You know, to help you do something, find something. Talking to a ghost is so weird. No one would believe me.”

“If you tell everybody you can talk to a ghost, they’ll put you in a mental hospital. Oh, and yes, you can do something for me. I want to go to the cemetery and see what kind of grave my family bought for me.”

“Okay, it’s a done deal; we’ll go tomorrow morning. What time do you want me to wake you up?”

“No need for that. I’ll be ready anytime.”

“Alright, see you tomorrow, Peter.”

“Yeah, good luck with that.”

In the morning, when I went out of the front door, I left it open for a few seconds, then I softly whispered, “Are you out, Peter?”

Then I opened the passenger door and, after a few seconds, asked, “Are you in, Peter?”

“Yes, I am. Thank you.”

“Okay, now, shut the door,” I said.

“How?” he replied.

“Okay, okay, I’m sorry.” Then, I went around and closed the passenger door.

“Okay, Peter, put your seat belt on.”

“Oh, you’re so funny!”

“Peter, do you want to drive?”

Then, ignoring my last question, he said, “Man, you need to replace this old piece of junk.”

“Do you want to walk? Do you want me to call you a taxicab, or do you want a limousine?”

“Sorry, sorry, can we just go already?”

As I started driving, I asked him, “Hey, Peter, do you go out of the house to walk or float around town?”

“I tried a couple of times, but I think the dogs can see me. They bark at me, and I can’t stand it. It isn’t charming. They want to bite me, and I want to kick them. Your little dog, what’s her name? Yes, Frida, when I go to the backyard, she won’t leave me alone. She follows me around and keeps barking all the time. It’s so annoying. I don’t go to the patio anymore, but Diego, the other dog, doesn’t know I exist. And he’s right.”

We had to look for his grave at the cemetery because he couldn’t remember where they buried him. When we found it, he said, “Those cheap bastards! Look at my wife’s grave site, top-of-the-line! Now, look at mine. The headstone looks secondhand, so small and ordinary. But at least someone brought me flowers, and they look fresh. There’s a note in them. Can you please read it for me?”

“Yes, Peter. It says, I miss you, Uncle Peter. I hope you’re happy wherever you are. I will always love you.” Signed by Nancy Shelby.

“Oh, my dear Nancy. My favorite niece.”

Back at the house, he asked me to write a letter to her.

“My dearest Anais Neess:

I’m still at my house. I’m stuck somehow. I made friends with the new tenant, and he’s helping me deliver this note to you. Please, believe me, this is not a joke. And please don’t be afraid. I left some money for you. You’re the only beneficiary. He will provide you with more details on how to obtain this money. I didn’t put this in my will because I didn’t want the rest of the family to know about it.

I will keep you in my heart forever. I love you, Nancy.

Peter Shelby”

After searching for a few minutes on my computer, I found a government site for unclaimed money—a Savings account under Peter Shelby’s name for $45,000. I wrote down some account numbers and other details, added a separate note to the letter, and sent it to Nancy’s address.

He said Nancy was a nice girl, and she might give me a commission for helping her get this money. I said I didn’t care. Then, I asked if he could show himself again as he did in the bathroom mirror, and he said, “I have no idea how that happened, but one time, while I was watching TV with your wife, I saw my reflection on the TV screen.”

“You watch TV with my wife?”

“Yes, all the time. I sit next to your wife all morning, but I disappear when she changes the channel to her Mexican soap operas. I like it when she listens to her music while cooking. We like the same kind of music except for her mariachi songs.”

“And how can you move things around or make noises if you say you can’t touch anything?”

“Oh, I don’t know. I might have telekinetic powers when I’m desperate or frustrated, but I’m not sure.”

I wanted to try another experiment with Peter, so I asked him to come out to the backyard with me.

“Okay, Peter. I want to paint your body, soul, or spirit with your permission. You stand right here in the middle of the patio. I’ll bring my spray paint gun and some white paint and see what happens, okay?”

“Okay, that sounds like fun,” he answered.

After I gathered all the necessary items, I asked if he wanted a mask, and he said, “What for?” Then I said, “Okay, close your eyes,” and he repeated, “What for?”

“Okay, just stand still,” I said and began to paint him. Then, my little dog Frida came and started barking around him. We couldn’t stop laughing out loud.

That’s when my neighbor’s head appeared above the fence and asked, “Hey, why are you painting your dog? Are you crazy or something?” Then, I realized he was right. Frida had white paint all over, and I didn’t know where Peter was, so I couldn’t stop laughing.

Before my wife returned home from work, I asked Peter if he wanted to do something the next day. “Yes, if you don’t mind, I’d like to go to church and talk with God because I don’t think he’s in this house.”

The following morning, after a long absence, I returned to church. I had been busy doing nothing. But I knew I didn’t need intermediaries, priests, or churches to talk to God.

When Peter finished with God, he whispered in my ear, “Let’s go. I’m ready.”

On our way home, he said, “I have a feeling that we won’t be able to be together or communicate anymore. I appreciate your friendship and your companionship very much. I hope to see you in my ‘other’ house someday.”

We found a woman knocking at the front door when we returned home.

“Hi, I live in this house. What can I do for you?” I asked. She seemed to be in her thirties; she had a quiet and tender beauty. She seemed a little shy.

“Hi, my name is Nancy Shelby. I believe I received a letter from you. At first, I thought it was a tasteless joke, so absurd and incredible. However, when I checked the account, I confirmed it was indeed true. I need to tell you how fortunate you are to be able to communicate with my Uncle Peter. He was such a good person. At his funeral, my mother told me my uncle Peter had paid my college tuition. I knew my mom didn’t have the means to afford it.”

“But who’s Anais Neess?” I asked her.

She smiled, “It’s a game of words, Anais Neess, or ‘a nice niece.’ I always loved it when he called me that.”

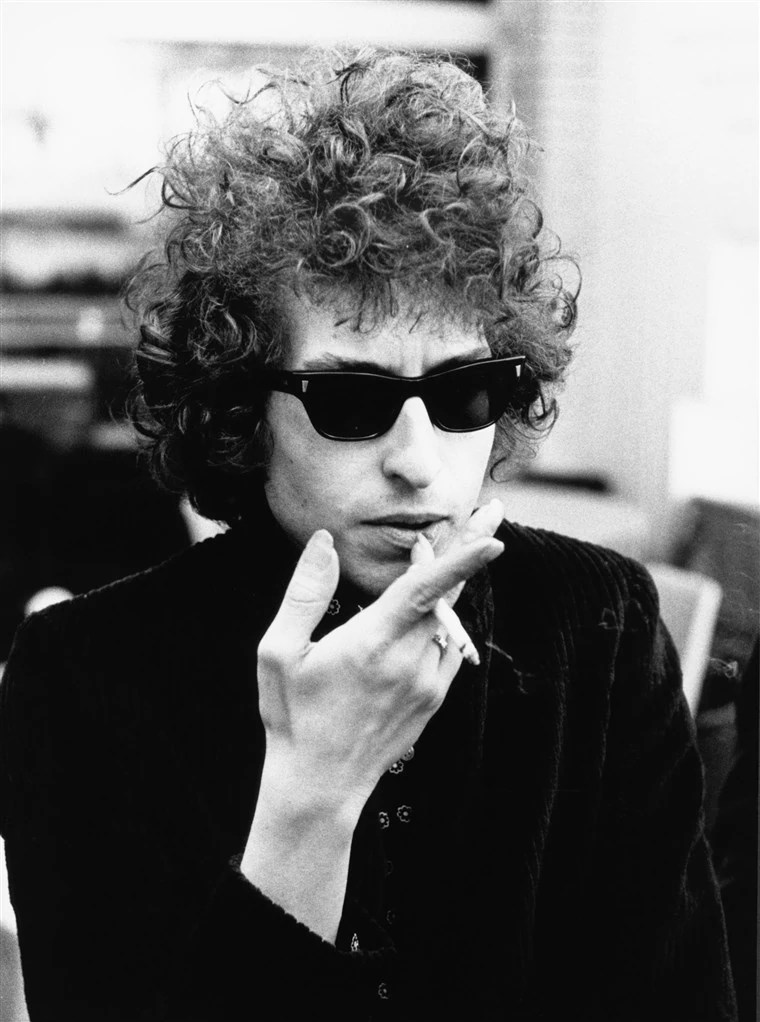

After that day, Peter disappeared from the house. I went crazy talking to him in every room, to no avail. There were no signs of him anywhere. I missed him a lot. Then, one day, I received a letter from Nancy, a note with a few words, a check for $5,000 made out to me, and, most importantly, a picture of Peter.

I keep that photograph on my desk, next to my computer, in his room.

THE END

Edmundo Barraza

Visalia, CA.

Nov-2010

U.S. Copyright Office

TXu 2-366-623

04-27-2923